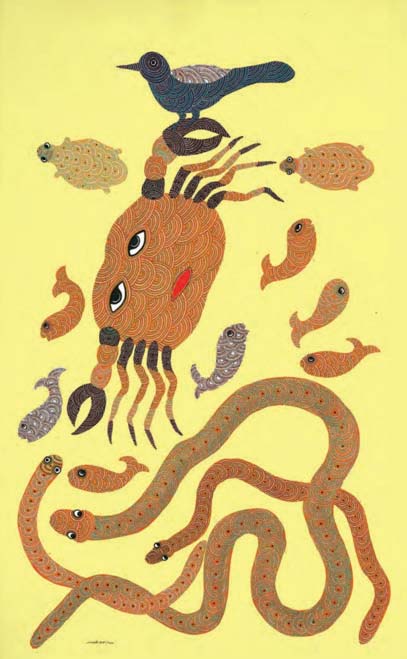

On 3 July 2001, a 39-year-old Gond tribal artist called Jangarh Singh Shyam on an Indian Council for Cultural Relations residency in Japan committed suicide caused by the unfamiliar environment he found himself isolated in. Jangarh’s genius had been discovered by the modernist J. Swaminath when setting up the Roopankar Museum in Bhopal as part of the Bharat Bhawan complex. He could be found painting (and selling, for a few hundred, and then a few thousand rupees) simple paintings that spoke of his love of his environment, life in the jungles of Bastar and his belief in forest deities and creatures. In time, he met artists such as M. F. Husain, was part of exhibitions curated by Jyotindra Jain, and eventually came to be recognised as the progenitor of the ‘Jangarh Kalam’, more popularly identified in his wake as Gond art.

Precocious values

On 25 April 2024, the late Jangarh’s Untitled canvas featuring what looks like a crab, turtles, fish, snakes and a solitary bird, sold for a whopping Rs. 50 lakh at a Pundole’s auction in Mumbai, setting a record for the artist, turning him into the star of the auction, even though a Raja Ravi Varma painting titled Mohini was the highest grosser at Rs. 17 crore. Many of us had actually expected to see Mohini sell for much higher—it was, after all, an image made familiar through oleographs from the Ravi Varma Press, and had an impeccable provenance, having been in the family that bought and ran the press till it was burned down in the 1970s. Ravi Varma’s auction record currently stands at Rs. 38 crore for his Yashoda Krishna, also sold by Pundole’s in 2023.

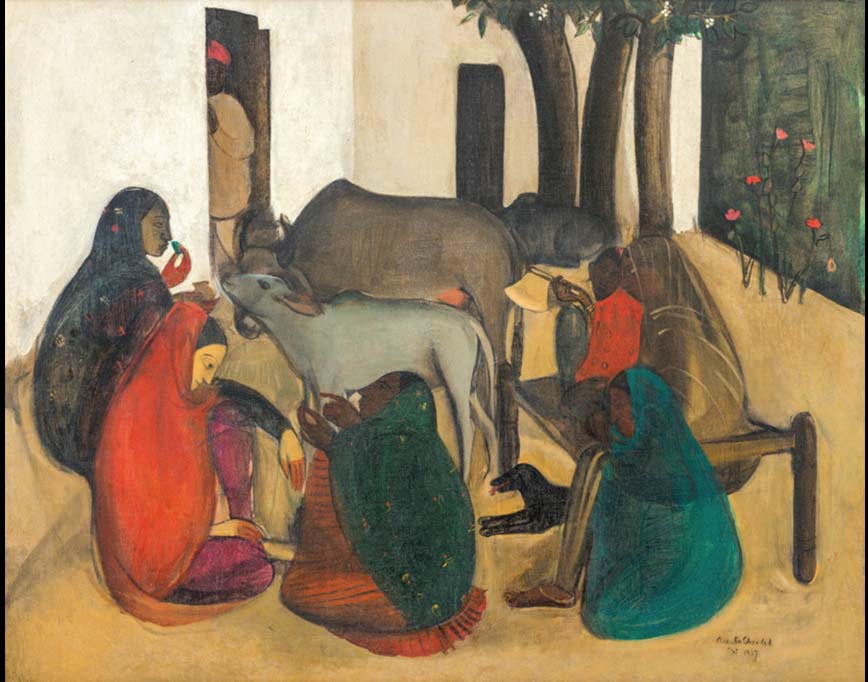

But Ravi Varma, widely perceived to be the father of Indian modernism, and certainly one of the most defining names in Indian art, is far from the highest-earning auction artist of Indian origin. Amrita Sher-Gil, who redefined the rules of Indian modern art, holds that current honour as the artist whose The Story Teller fetched Rs. 61.8 crore at Saffronart’s live New Delhi auction, also in 2023. The painting of a rural scene defined Sher-Gil’s art following her return to India ahead of the outbreak of the Second World War after the half-Hungarian, half-Indian artist married her American cousin in Hungary where he was serving as an army doctor. Famously, she sold almost no works in her tragically short life, dying at the age of 28 of a miscarriage in Lahore in 1941 in an operation believed to have been mishandled up by her own husband.

The gentle and soft-spoken S. H. Raza, whose paintings are the toast of the collection of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, became the artist claiming the second-highest value with his Gestation fetching Rs. 51.75 crore at Pundole’s September 2023 auction in Mumbai. A favourite among most collectors, Raza’s prices have been blazing a fiery trail ever since his retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris last year shone the global spotlight on him.

Humiliatingly high

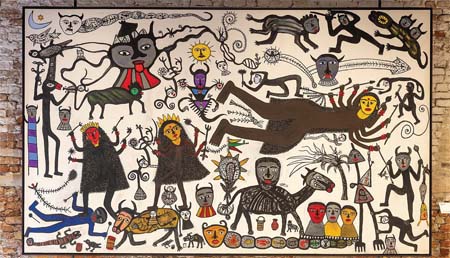

F. N. Souza, whose birth centennial this year is being celebrated with exhibitions in India and abroad, and who proclaimed himself to be the world’s greatest living artist following the death of Pablo Picasso in 1973, has often appeared in auctions commanding steep prices. Till recently, it was Birth, earlier owned by Tina Ambani before it was acquired by Kiran Nadar, that had remained his auction benchmark before it was replaced in March 2025 by his Lovers, auctioned by Christie’s in New York for a sum of Rs. 40 crore. Intolerant of most other artists, Souza would have found the slight of of not commanding the highest values humiliating, particularly with the top spot occupied by a woman artist, especially since he had spent much of his life painting female nudes in a misogynistically denigrating manner. That he had inculcated Raza into the Progressive Artists’ Group he founded in 1947 would add to his further embarrassment.

And what of M. F. Husain, for decades India’s most popular and well-known artist who everyone loved or disliked in equal measure, who was considered India’s most prolific and expensive artist? Dear reader, Husain sa’ab’s market is finding it difficult to hold its own with his works still to catch up to the auction records of the likes of Tyeb Mehta (Rs. 45 crore), V. S. Gaitonde (Rs. 42 crore) or Akbar Padamsee (Rs. 25 crore), all of them achieved over the last few years. But his retrospective, currently on view in Vienna, will accelerate his prices. Every auction of Indian or South Asian art—and there are now several every year—brings heart-stopping moments about fresh records being constantly established, and not just in the top tier but among artists and sculptors such as M. V. Dhurandhar, Jehangir Sabavala, Adi Davierwalla, Piloo Pochkanawalla, A. Ramachandran, Krishen Khanna, Satish Gujral and so many more whose works have started a scavenger hunt among collectors wanting to add them as trophies on their walls.

On steroids

The Indian art market has been in a sweet spot ever since Covid when, contrary to all imagination, it accelerated and picked up pace. Nor has it slowed down thereafter, and at less than 0.5 per cent of the global art market, currently valued at Rs. 3,000 crore, it is upping and betting big on growing exponentially on the tailwinds of a strong economy. In a recent opinion piece in a newspaper, former diplomat and lately a political figure, Pavan Varma observed, “For a three trillion economy like ours, the art market should be at least six times more.” When it reaches that potential—and in the current environment it will likely be sooner than later—it will have set the art market scorching even further with the masters commanding prices over Rs. 100 crore and more, and a wider swathe of artists getting their due among whom I can already see the likes of Madhvi Parekh and Manu Parekh, currently enjoying an eye-popping outing at the prestigious Venice Biennale, enjoying a groundswell of collectability.

But that is hardly news for artists who gain from international shows. In a matter of just a decade, the late Nasreen Mohamedi has gone from being little known to fetching, at an auction last month, a record price of Rs. 11 crore. For some, buying a house in a prestigious neighbourhood is cheaper than buying a painting by an equally prestigious artist. And what’s a house without its art?

In a market that is riding on endorphins, artists across the spectrum have benefitted. For collectors, though, it is a Hobson’s choice—while increased values mean their current assets have shot up exponentially in value, the market for new acquisitions has become equally expensive, even though it has only proved what so many in the art world have been saying for so many years—that art is a tradeable asset class, albeit not instantly liquid, but one in which there is little scope for losing value.

Genesis of the collector

A new breed of younger, informed collectors has now appeared on the scene—whether second- or third-generation collectors, or those schooled overseas and informed about the advantages of diversifying one’s asset portfolio, those with strong aesthetics and a passion for art, those coming from tier two and three towns wanting to belong to that breed styled as ‘art collectors’, or others following urban lifestyle trends in which owning art puts them at an advantage. Conversations about art are, after all, intellectually satisfying the way owning a pair of expensive shoes or bag or pieces of jewellery cannot be—unless you’re talking emeralds of the kind Nita Ambani wore to her son’s pre-wedding bash—now that’s a conversation starter of a kind very few of us can match.

Most collectors like to hedge their bets. A work by Raza or Husain might be desirable for the nod from the social cognoscenti that it appeals to, but it needs a big purse and a bigger heart to put all one’s money in it. So, collectors like to spread the portfolio to include artists from today’s generation who appeal across multiple segments based on their aesthetics—Paresh Maity, Satish Gupta, Seema Kohli, K. S. Radhakrishnan, Jayasri Burman—even as they dip their toes into the luminaries of contemporary art such as Subodh Gupta, Bharti Kher, Jitish Kallat, G. R. Iranna, Atul Dodiya who burnt their fingers when the art bubble burst in 2008 but have recently come back into their own to represent the anxieties and hopes of their generation and the times we live in. And here’s an adage to live by: today’s contemporaries will be tomorrow’s masters.

Faking it!

With values scorching the marquee, it brings with it its own basket of problems among which are issues of authenticity. For Indians who are bargain-hunters, the chances of getting duped can only grow when price becomes the only criterion for a purchase. Faking — a problem the world over — is now testing the shores in India. And why not? In the absence of a regulatory body, cleverly crafted fakes and authenticity papers by charlatans end up duping collectors who do not undertake the trouble of proper diligence, the greed or lure of an impossible bargain getting the better of their sound judgement. It is another matter that so many buy deliberate fakes in the form of works that are sold as copies of popular artists down to their signatures. A word to the wise: such purchases could run foul of an artist engaging a lawyer to safeguard the intellectual property rights of a work of art, thereby costing one much more in the long run than it is worth.

Don’t shy from the paperwork

There is a way to avoid being taken for a ride, of course. Auction houses conduct rigorous due diligence and can be a good bet when testing the waters as a potential collector, though prices can vary and one could get carried away and end up paying more than what one had bargained for in the heat of the moment. (Also, it is difficult to calculate the buyer’s premium and taxes, which are in addition to the hammer price – something to keep in mind when bidding.) Or, ask around at well-established galleries where prices will likely be higher but they are unlikely to associate with fakes, any hint of which will smear a reputation built up over decades. Finally, of course, you must train your own eye, something that can only happen with constant exposure to high quality art. Visit galleries frequently, attend openings, speak with artists (though most will not sell directly and will refer you to their galleries), share your interests (as well as budgets) with gallery owners as well as their sales representatives, attend talks, sift through art-related books and catalogues, build friendships within the art community, and look for mentors.

I like to see what other collectors are buying, though this is not always known, especially now that most auctions are conducted less in the sales room and more over telephone and online bids. But listen to – oh, well – old-fashioned gossip. See who collectors you admire are acquiring. Plan your budget and try not to exceed it (it’s so easy to). Of course, you must make up your mind what shape you want your collection to take. It could be eclectic and diverse – my preference. Or you might want it to be tightly focused on only a few artists. Maybe collect works by Bengal School artists, or the Progressives, or perhaps only abstract paintings. What about themes such as Himalayan landscapes, or mythological works, or only watercolours? Some collect works based on an artist’s ethnicity; someone I know is collecting artworks by only those associated with Baroda’s Faculty of Fine Arts, whether faculty or alumni. Another is collecting artworks created in the year of his birth.

![]()

When buying a work of art, ensure that you have all the paperwork you will need in the future when values have risen even higher than those today. These include signed provenance papers (who the work belonged to previously; or whether bought directly from a gallery/artist); an authenticity certificate from the gallery or artist; any publications the work might have been appeared in such as a book or newspaper or catalogue; and the cherry on the cake would be a photograph of the artist with the artwork. Keep these safe in storage – they are as precious as your property papers, if not more.

The one that got away

The one that got away

Stories are endemic of collectors who bought art at what can now be considered throwaway prices but remember that art has always been expensive and elusively out of reach. It is a financial stretch to buy works that have value in the current scenario. You can, of course, invest in beginners provided you have the eye to see who has the makings of a good artist with credible art as well as staying power and the backing of solid galleries that will put their money into promoting the artist.

But even the best-intentioned plans can go amiss when trusting these beginners. I was drawn to a young artist whose work I admired and bought a few works from him when I could scarcely afford them. The artist had great promise, a well-known gallery had held his exhibition in New Delhi and published a catalogue to accompany it. Things might have gone well but the young lad, from an impoverished background in a small town, experienced heady fame. He also began to nurse a fondness for alcohol that led rapidly to addiction and his death in a road accident, burying his dream before he had a chance at creating either a market or a legacy. Lucky for me, I like his art even though it serves as a reminder of a fate’s fickle promise gone awry.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

![]() Kishore Singh is a former columnist and editor with experience in journalism and publishing. He has written several books, the most recent on art and artists.

Kishore Singh is a former columnist and editor with experience in journalism and publishing. He has written several books, the most recent on art and artists.