Throughout time, cities have served as crucibles of civilisations, creators of wealth, and cradles of diverse cultures, giving birth to innovative ideas that propel humanity forward.

Some of the world’s leading cities today find their genesis in post-medieval Europe when trade routes expanded, and the emergence of commerce and industry created a prosperous merchant class across the seas. This newfound wealth not only enriched cities but also triggered a virtuous cycle of prosperity and infrastructure development. Ports and docks supported growing businesses. Inventions revolutionised work, leading to increased productivity, higher profits, and the rise of affluent urban centres. This prosperity fostered vibrant artistic and cultural expressions, contributing to the splendour of today’s metropolises. Cities in India, too, were touched by this burgeoning global network – most prominently, Mumbai and Kolkata.

![]()

Asian contemporaries such as Shanghai, Singapore, and Seoul ascended as global urban models to rival Western counterparts. In the west, New York and London continually reinvent themselves, maintaining their status as the world’s leading cities. While some cities adeptly navigated rapid changes, others deteriorated, leaving behind fragments of a once-grand past. Whether originating as ports, trading hubs, or pilgrimage centres, or even artificially created as capital cities or industrial towns, the greatest cities have continuously adapted, evolving to meet the ever-changing demands of their environments and humanity.

India as the reluctant urbaniser

India’s urban morphology was shaped fundamentally in this period, laying the foundations for our modern towns and cities. Not all Indian cities evolved equally. Some grew tremendously in the 20th century – as much a function of political realignments as economic imperatives. Others found a niche and an equilibrium, remaining static for most of the 20th century, which extended well into the first decade-and-a-half of the 21st century as well. Others, still, remained as they always were – eternal and culturally rich. Kashi, or Varanasi, is one such example. The words of Mark Twain resonate profoundly: “Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older than even legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.”

Nevertheless, India’s cities contained only a fraction of its population. Gandhi ji’s quote comes to mind, “India lives in its villages.” That, perhaps, was the abiding memory of India of the 20th century; a newly independent country, residing in its villages and grappling with overpopulation and poverty. Despite big cities such as Delhi and Mumbai, India was largely—and perhaps, fairly—considered a ‘reluctant urbaniser’.

This somewhat lengthy preamble is presented here to make the reader familiar with the perception of India and its urban systems (or lack thereof) at the end of the Second World War. And yet, the irony was that more Indians resided in its cities than the populations of many countries at the time! 17 percent of India’s 350 million people, or roughly 60 million people, lived in India’s towns and cities in 1951.

Over the last 75 years, these numbers have increased considerably to 34 percent of 1.4 billion, or roughly 470 million people. By 2030, it is estimated that more than 40 percent of India’s population, i.e., 600 million people—a tenfold increase since independence—will live in its urban areas. This means that twice as many people will live in urban India by 2030 than the current populations of England, France, Germany and Italy combined.

The natural questions that follow are: Was India prepared to handle such urbanisation? Did it manage this massive migration well? Did it capitalise on the agglomeration effects of urban economies and lead to prosperity – as had been observed in the Miracle Economies of Asia, and latterly, China, in the same period? The answers, unfortunately, are not promising. While Indian cities demonstrated notable economic growth, expanding not only in physical size but also in diverse socio-economic aspects, they most certainly did not realise their full potential.

Urban development in India was neglected for decades

Successive governments prioritised rural development. It wasn’t until 2014 that India finally witnessed a long-term vision and a concerted effort to rejuvenate our static and, in some cases, stagnating cities. Since I was invited to join the Council of Ministers in September 2017 and given charge of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs for the Government of India, I have had the privilege of being associated with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision for multi-faceted urban rejuvenation. In many ways, the integrated nature of these urban interventions is a microcosm of India’s development ambitions.

![]()

The Prime Minister unleashed a comprehensive urban development programme in 2014-15 through the introduction of flagship “missions”, aiming to have a transformative impact on people’s lives via inclusive, participatory, and sustainable development approaches. A standout feature of these missions has been the substantial upswing in investments dedicated to urban development. The government has led the way by significantly augmenting budgetary allocations.

![]() Over the preceding 10-year period (2004-05 to 2013-14), a total of Rs. 1.57 lakh crores (15 billion GBP) were allocated. In contrast, the cumulative budgetary allocations from 2014 onwards have soared to more than Rs. 18 lakh crores (170 billion GBP) – an almost 12-time increase. Additionally, where the 13th Finance Commission allocated Rs. 23,111 crores (2.2 billion GBP) to Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) during the period from 2010-11 to 2014-2015, the 15th Finance Commission allocated Rs. 1,55,628 crores (14.8 billion GBP) to ULBs for the timeframe spanning 2021-22 to 2025-2026. This is the kind of support our cities needed to recover from decades of criminal neglect.

Over the preceding 10-year period (2004-05 to 2013-14), a total of Rs. 1.57 lakh crores (15 billion GBP) were allocated. In contrast, the cumulative budgetary allocations from 2014 onwards have soared to more than Rs. 18 lakh crores (170 billion GBP) – an almost 12-time increase. Additionally, where the 13th Finance Commission allocated Rs. 23,111 crores (2.2 billion GBP) to Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) during the period from 2010-11 to 2014-2015, the 15th Finance Commission allocated Rs. 1,55,628 crores (14.8 billion GBP) to ULBs for the timeframe spanning 2021-22 to 2025-2026. This is the kind of support our cities needed to recover from decades of criminal neglect.

The transformational success of India’s urban missions

Guided by the Gandhian principles of Antyodaya se Sarvodaya (saturation of service by reaching the most vulnerable) and self-sufficiency, the Modi government devised a novel three-tiered strategy of development to suit the needs and context of individual cities. A ‘one size fits all’ model would not have worked for India’s bewilderingly diverse urban areas.

In the bottom—and widest—tier, we have the Swachh Bharat Mission (Clean India Mission) where all the urban areas in India were required to become ‘Open Defecation Free’ to achieve the basic tenets of cleanliness and hygiene. Accompanying it is the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) mission which involved 500 cities with populations of more than 100,000 developing sustainable water and sewerage systems, among other civic amenities. Both these missions are now in their second avatars. Alongside this, we have the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (‘Housing for All’ mission) which has sanctioned close to 12 million houses to India’s urban poor.

![]()

Together, these three missions address various facets of urban life, spanning cleanliness, sustainable water and sewerage systems, and housing, among others, with the overarching objective of achieving comprehensive urban development. Nowhere else has such planned urbanisation been witnessed – and on such a scale!

I spoke earlier of the eternal city Kashi and Mahatma Gandhi. Few will know that the Mahatma visited the city in 1916 to address a gathering of students in various colleges, including at the Benares Hindu University. Disturbed by the filth he saw on the streets of the city and in its famous Vishwanath temple, he famously said, “is it right that the lanes of our sacred temple should be as dirty as they are? The lanes are tortuous and narrow. If even our temples are not models of roominess and cleanliness, what can our self-government be?” His lament went unanswered, even after we had gained independence. India continued to plod along until 2014.

It took a revolutionary address from the ramparts of the Red Fort on 15th August 2014 (India’s independence day) by the then newly elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi to dispel the taboo around a problem which we had all been ignoring. Some sneered at the idea that a Prime Minister would speak of toilets and Open Defecation Free neighbourhoods in his first independence day address. Yet, this is what India desperately needed. And the Modi government delivered. It is fitting that the Parliamentary constituency of Varanasi is represented by the Prime Minister, symbolising a remarkable journey from Gandhi’s lament about the cleanliness of a temple town to Prime Minister Modi’s resolute commitment to cleanliness.

I consider the Swachh Bharat Mission to be the fulcrum of India’s urban transformation. It is a shining example of the holistic approach adopted towards urban reforms and sustainability. It targeted the most vulnerable sections of our urban society, and reinforced core messages of sustainability. Not only have we constructed over 6.9 million toilets while increasing waste processing capacity from a meagre 17 percent in 2014 to nearly 77 percent today, we have also brought about holistic behavioural change in our citizens towards Swachhata (cleanliness). Somewhere along this journey, the Swachh Bharat Mission morphed into a ‘Jan Andolan’ (a people’s movement).

In the next phase of the programme—with nearly 2.5 times of government funding in comparison to the first iteration—the mission will provide impetus to city governments to become ‘garbage free’ by planning measures for sludge management, waste water treatment, source segregation of garbage, reduction in single-use plastics, management of construction and demolition (C&D) waste, and bio-remediation dump sites. It is our hope and belief that, by 2026, we will have eliminated all garbage dumpsites in urban India.

The AMRUT mission compliments the Swachh Bharat Mission as it aims to make all our cities ‘Water Secure’ by providing 100 percent coverage of water supply to all urban households in the country through 26.8 million tap connections and 26.4 million sewer connections. Apart from the infrastructural remit, this mission has also focused on reforms. Over the last 7 years, we have seen 12 cities issue municipal bonds worth Rs. 4,384 crores (413 million GBP). We have incentivised transit-oriented development; adoption of Transferable Development Rights; integration of blue and green infrastructure through nature-based solutions; in-situ slum rehabilitation; and GIS-based master planning. Several best practices are now flourishing and being replicated across the country, as well as in the Global South.

Alongside the basic needs of water and sanitation, the fundamental need of housing was given fillip with the ‘Housing for All’ mission. Nearly 12 million houses have been sanctioned by the government, wherein more than 11.3 million houses have already been grounded and beneficiaries have already moved into nearly 7.9 million housing units. Most of the housing has been developed by utilising energy-efficient and low-carbon building technologies that have incorporated sustainable land-use practices.

In the second tier of the Modi government’s strategy for urban development, the Smart Cities Mission is being implemented in 100 competitively selected cities of India. The mission aims at a transformational revamp of the physical, social, economic and institutional infrastructure of these cities through the application of smart solutions. It has successfully embedded a culture of innovation in urban development. The tangible impact of the Smart Cities Mission is there for all to see: with a total project cost of more than Rs. 1.7 lakh crores (16 billion GBP), and nearly 8,000 urban projects across domains as diverse as waste management, mobility, e-health, and solar energy sanctioned.

Going beyond mere asset creation, this mission has ingrained a commitment to ‘excellence’ in urban governance. For example, every Smart city under the mission has a Smart City Centre (also referred to as Integrated Command and Control Centre). This is, and will be, the city’s nervous system where digital technologies are integrated to social, physical and environmental aspects of the city to provide centralised monitoring and decision-making capabilities to urban administrators. Instead of investing heavily on permanent infrastructure, our smart cities have followed a tactical approach to develop vibrant urban spaces in a cost-effective and swift manner through the concept of placemaking which is a multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and management of public spaces.

Finally, in the top tier, we have brought about a paradigm shift in India’s mobility agenda in select large cities. We are massively supporting public transport and Non-Motorised Transport (NMT) options across the country through large investments, especially in metro rail systems and e-Buses.

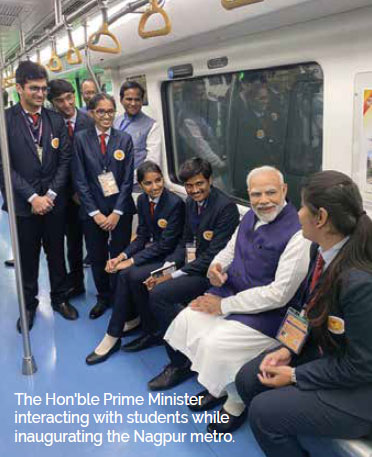

We now have the fifth-largest metro network in the world with around 905 kms of metro lines laid. After the construction of another 892 kms of planned metro network, India will become the second-largest metro network in the world.

Digital reforms and achievements in the last nine years

Technology and data are important enablers in the journey of a smart, prosperous and resilient city. Technology helps you sense the city, oversee its operations, and build connected communities. Emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Blockchain, are helping our cities create innovative solutions to complex urban problems and concurrently enhancing their capabilities to harness these advancements. The Prime Minister has mandated the use of technology for the public good. The government’s programmes such as the Digital India Mission and Start Up India are also helping develop capacities. Data safety and privacy, fundamental rights of citizens, are unbroachable, making protection against data thefts and cyber threats a paramount focus.

Lifting the most vulnerable sections of urban society

These missions, among other initiatives, exhibit the Prime Minister’s philosophy of Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Prayas, Sabka Vishwas (with everyone’s support, development for everyone, with everyone’s effort, with everyone’s belief). They have spurred policy focus towards reducing inequality and enhancing the quality of life of citizens in an inclusive manner.

![]() Before 2014, the vulnerable and marginalised sections of our urban society were ignored. The built environment around them was usually informal and ill-equipped. Their aspirations, as a consequence, remained unrealised. The Modi government viewed this inherent informality of urban India as an untapped opportunity rather than a hindrance. It was a chance for us to bring millions of informally employed workers into the net of the government’s welfare programme.

Before 2014, the vulnerable and marginalised sections of our urban society were ignored. The built environment around them was usually informal and ill-equipped. Their aspirations, as a consequence, remained unrealised. The Modi government viewed this inherent informality of urban India as an untapped opportunity rather than a hindrance. It was a chance for us to bring millions of informally employed workers into the net of the government’s welfare programme.

Around 20% of India’s urban population lives in informal settlements. Naturally, it was these people who became the primary focus of the government’s initiatives. There was a distinct mandate to identify to identify those being left behind, understanding the manner and areas in which it was occurring. Two programmes of the Government of India have addressed the problem of occupational vulnerability in urban areas, especially during the pandemic.

The first, the ‘PM Street Vendor’s Aatmanirbhar Nidhi’, or the PM SVANidhi scheme, was launched in June 2020 to provide a micro-credit facility as working capital loans to street vendors. This cash infusion has not only made them self-reliant but has also harnessed a micro-economy of entrepreneurship in urban areas. In all, almost Rs. 10,000 crores (928 million GBP) worth of loans have been disbursed to more than 5.6 million unique street vendors.

The second, the National Urban Livelihood Mission is targeted at strengthening livelihoods of the urban poor through skill up-gradation, entrepreneurship development, and employment creation. More than 889,000 Self-Help Groups (SHGs) comprising more than 9.1 million members have been formed under this programme. Nearly 1.51 million beneficiaries have been trained, while more than 73,000 beneficiaries have either been linked with banks or been provided access to loans in this mission. The programme has focused on increasing wage employment and self-employment opportunities in emerging markets in India’s urban areas, thus also considerably moving the needle on the formalisation of the economy.

Enhanced dignity and agency for women in urban India

Enhanced dignity and agency for women in urban India

The demographic which has reaped the greatest benefit from these missions has been our women. The PM’s vision to empower women and promote gender equality is reflected in the fact that all houses under the ‘Housing for All’ mission are either directly or jointly owned by women. Many women in urban areas previously engaged in informal livelihoods, facing financial exclusion. However, with assets now registered under their names, they have gained life-altering financial security.

Our missions have served as substantial employment generators, particularly for women workers who form the predominant workforce in the construction industry. It is estimated that the Prime Minister’s housing mission was directly or indirectly responsible for 6.87 billion person days of employment generation, and yielded 24.5 million jobs.

What lies ahead: urban development is key in realising SDGs

Despite these transformational gains, a lot still needs to be done if we are to achieve the national goal of becoming a developed country, or Viksit Bharat, by 2047. Rather than prescribing solutions in a piecemeal manner, we are encouraging our local urban governments to look at their cities as ‘system of systems.’ The next phase of our urban journey will involve integrating urban services through stronger cross-functional governance and digital infrastructure – the groundwork for which has already been laid.

The focus is on building intelligence and generating insights rather than just creating data footprint. Going forward, it could be argued that a regional outlook towards our cities and towns may be best placed to capture the economic characteristics of cities which usually transcend administrative jurisdictions, and helps identify suitable policies for local economic development. Cities can be vital in diversifying economic activity and reducing our dependence on global value chains.

At this inflection point for India—and the world—where our response to myriad socio-economic challenges will determine the country’s trajectory for decades, if not centuries, to come, cities are the future of India’s development. They are not just the proverbial ‘engines of growth’, but also serve as hubs of innovation and drivers of collective action. Indian cities already constitute over 60 percent of India’s GDP – a figure that is expected to rise to 70 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050. An Oxford Economics Report predicts that by 2035, all the top ten fastest-growing cities worldwide will hail from India. It is crucial, therefore, to glean valuable insights from past efforts in urban development and harness the foundation laid through our various urban development endeavours for leapfrogging success in the future.

India’s model of urban development: A beacon for the world

India’s urban agenda will be integral in our pursuit of the tenets of economic progress, social equality and environmental sustainability. Whether it is reducing poverty and income inequality; developing universal access to health, education and digital technology; increasing livelihoods through industry and innovation; or optimising our energy consumption, urban areas will be crucial drivers and facilitators in achieving the respective goals.

In an eventful but ultimately enervating year for global governance, few countries emerged with any credit. India was the significant outlier. Its rise has signalled the emergence of a global order where the ambitions and concerns of the Global South will be central in global conversations. No trend is as inevitable as urbanisation. The Global South will witness a drastic increase in its urban populations in the decades to come. The recently concluded G20 under India’s Presidency included the landmark communiqué of the Urban 20 working group which produced the highest consensus ever, of more than 100 countries, on the way forward for global urban development.

India has offered a model of urban development that is inclusive, sustainable, and replicable. We have shown that urbanisation is an opportunity to grow sustainably. It has been the anchor in our vision for development and will continue to play a pivotal role in our future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hardeep Singh Puri is Union Minister of Housing & Urban Affairs and Petroleum & Natural Gas. A career diplomat who has served numerous assignments for the country, he writes often on policy and development issues.